When writing programs, developers have a choice of whether they want their work to be public or private. Programs that are made public are called “open source” and ones that are not are called “closed source”. In both cases the developer can share a program with the world as a website or iPhone app, or whatever, but in the case where the code is shared publicly it’s also possible for anybody anywhere in the world to change the program to make it better. (For more detail on this and other jargon, see the definitions at the end.)

This is very cool!

But I hear you asking, “How do I, a non-developer, make use of this system to make the world a better place?” I’m glad you asked — this article is for you.

And then there was Git

Git is an extremely popular system that developers use to keep track of the code they write. The main thing it does is make it so that two developers can work on the same file, track their individual changes and then combine their work, as you might do in Microsoft Word. Since all programs are just collections of lots of files that are together known as a “repository”, this lets a number of developers work together without tramping on each others changes.

There are a million ways to use Git but lately a lot of people use Git through a website called Github. Github makes it super-easy to use Git, but you still need to understand a few steps that are necessary to make changes. The basic steps we’ll take are:

- You: Find the file

- You: Change the file and save your changes

- You: Create a pull request

- The manager (me or somebody else): Merges the pull request, making your changes live

For the purpose of this article, I’ve created a new repository as a playground where you can try this out.

The playground is here: https://github.com/mlissner/git-tutorial/

Go check out the playground and create a Github account, then come back here and continue to the next step, changing a file.

Make your change

Like the rest of this, the process of making a change is actually pretty easy. All you have to do is find the file, make your change, and then save it. So:

Find the file

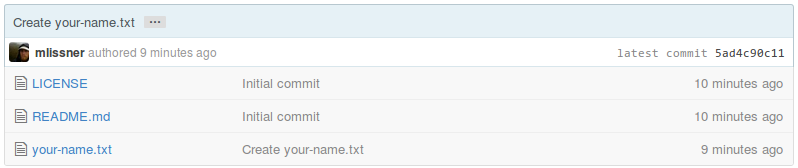

When you look at the playground, you’ll see a bunch of files like this:

Click the file you want to edit. In this case, it’s we’ll actually be changing file called “your-name.txt”. Click it.

Once you do that, you’ll see the contents of the file — a list of names, mine at the top — and you’ll see a pencil that lets you edit the file.

Click the pencil!

Change the file

At this point you’ll see a message saying something like:

You are editing a file in a project you do not have write access to. We are forking this project for you (if one does not yet exist) to write your proposed changes to. Submitting a change to this file will write it to a new branch in your fork so you can send a pull request.

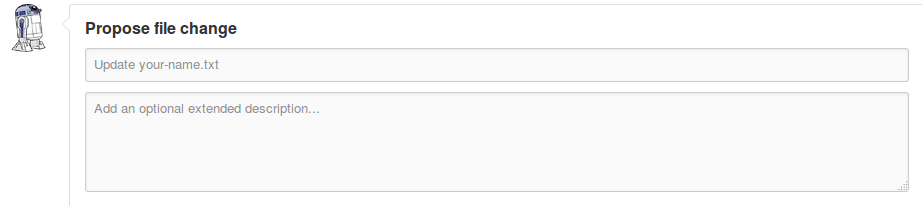

Groovy. If you ignore both the jargon and the bad grammar, you can go ahead and add your name to the bottom of the file, and then you’ll see two fields at the bottom that you can use to explain your change:

This is like an email. The first field is the subject of your change, something brief and to the point. The second field lets you flesh out in more detail what you did, why it’s useful, etc. In many cases — like simply adding your name to this file — your changes are obvious and you can just hit the big green “Propose file change” button.

Let’s press the big green button, shall we?

Send a “pull request”

At this point you’ll see another form with another somewhat cryptic message:

The change you just made was written to a new branch in your fork of this project named patch-1. If you’d like the author of the original project to merge these changes, submit a pull request.

I think the important part of that message is the second sentence:

If you’d like the author of the original project to merge these changes, submit a pull request.

Ok, so how do you do that? Well, it turns out that the page we’re looking at is very similar to the one we were just on. It has two fields, one for a subject and one for a comment. You can fill these out, but if it’s a simple change you don’t need to, and anyway, if you put stuff on the last page it’ll just be copied here already.

So: Press the big green button that says “Create pull request”.

You’re now done, but what did you do, exactly?

Let’s parse what’s happened so far

At this point, you’ve found a file, changed it, and submitted a pull request. Along the way, the system told you that it was “forking this project for you” and that your changes were, “written to a new branch in your fork of this project”.

Um, what?

The most amazing thing that Git does is allow many developers to work on the same file at the same time. It does this by creating what it calls forks and branches. For our purposes these are basically the same thing. The idea behind both is that every so often people working on a file save a copy of the entire repository into what’s called a commit. A commit is a copy of the code that is saved forever so anybody can travel back in time and see the code from two weeks ago or a month ago or whatever. 95% of any Git repository is just a bunch of these copies, and you actually created one when you saved your changes to the file.

This is super useful on its own, but when somebody forks or branches the repository, what they do is say, “I want a perfect copy of all the old stuff, but from here on, I’m going my own way whenever I save things.” Over time, everybody working in the repository does this, creating their own work in their own branches, and amazingly, one person’s work doesn’t interfere with another’s.

Later, once somebody thinks that their work is good enough to share with everybody, they create what’s called a “Pull Request”, just like you did a moment ago, and the owner of the repository — in this case, me — gets an email asking him or her to “pull” the code into the main repository and “merge” the changes into the files that are there. Once this is done, everybody gets those changes from then on.

It’s a brilliant system.

My turn: Merging the pull request

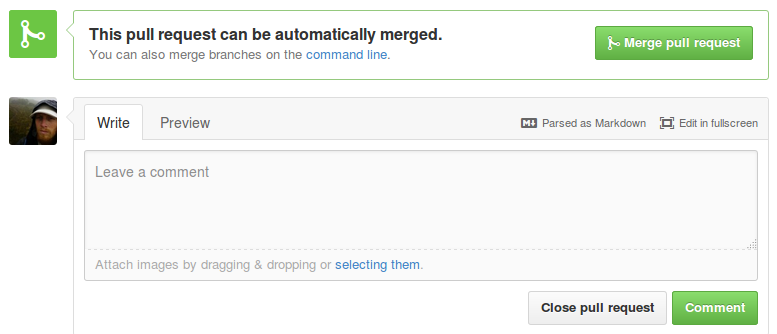

When you created that pull request a moment ago, you actually sent me an email and now you have to wait for me to do something. Eventually, I’ll get your email, and when I do I’ll go to Github and see a screen like this:

I’ll probably make a comment saying thank you, and then I’ll press the Big Green Button that says, “Merge pull request”.

This will merge your changes into mine and we’ll both go about our merry way. Mission accomplished!

Why this works so well

This system is pretty amazing and it works very well for tiny little projects and massive ones alike (for example, some projects have thousands of active forks). What’s great about this system is that it allows anybody to do whatever they want in their fork without requiring any permission from the owner of the code. Anybody can do whatever they want in their fork and I’m happy to see them experimenting. That work will never affect me until they issue a pull request and I merge it in, accepting their proposed changes.

This process mirrors a lot of real world processes between writers and editors, but solidifies and equalizes it so that there’s a right way to do things and so that nobody can cause any trouble. The process itself can be a little overwhelming at first, with lots of jargon and steps, but once you get it down, it’s smooth and quick and works very well.

As you might expect, there are tons of resources about this on the Web. Some really good ones are at Github and there are even entire online books going into these topics. Like all things, you can go as deep as you want, but the above should give you some good basics to get you started.

Some Definitions

-

Open vs Closed Source: This is a topic entire theses and books have been written about, but in general open source is way of creating a program where a developer shares all of their code so anybody can see it. In general when a program is open source, people are welcome to edit the code, help file and fix bugs, etc. On the other hand, closed source development is a way of creating a program so that only the developers can see the code, and the public at large is generally not welcome to contribute, except to sometimes email the developer with comments.

In a way, the product of open source development is a combination of the code itself plus the program it creates, while in closed source projects the product is the program alone. There are thousands of examples of each of these ways of developing software. For example, Android and the Linux Kernel are open source, while Microsoft Word and iPhones are not. (See how I couldn’t link to the latter two?)

-

Repository: A collection of files, images, and other stuff that are kept together for a common purpose. Generally it’s a bunch of files that create a website or program, but some people use repositories for all kinds of things, like dealing with identity theft (shameless plug), holding the contents of this very webpage (shameless plug), or even writing online books teaching lawyers to code (not a shameless plug!).

-

Pull request: A polite way to say, “This code is ready to get included in the main repository. Please pull it in.”

-

Merging: The process of taking a branch or fork and merging the changes in it into another branch or fork. This combines two people’s work into a single place.

I love getting feedback and comments. Make my day by making a comment.